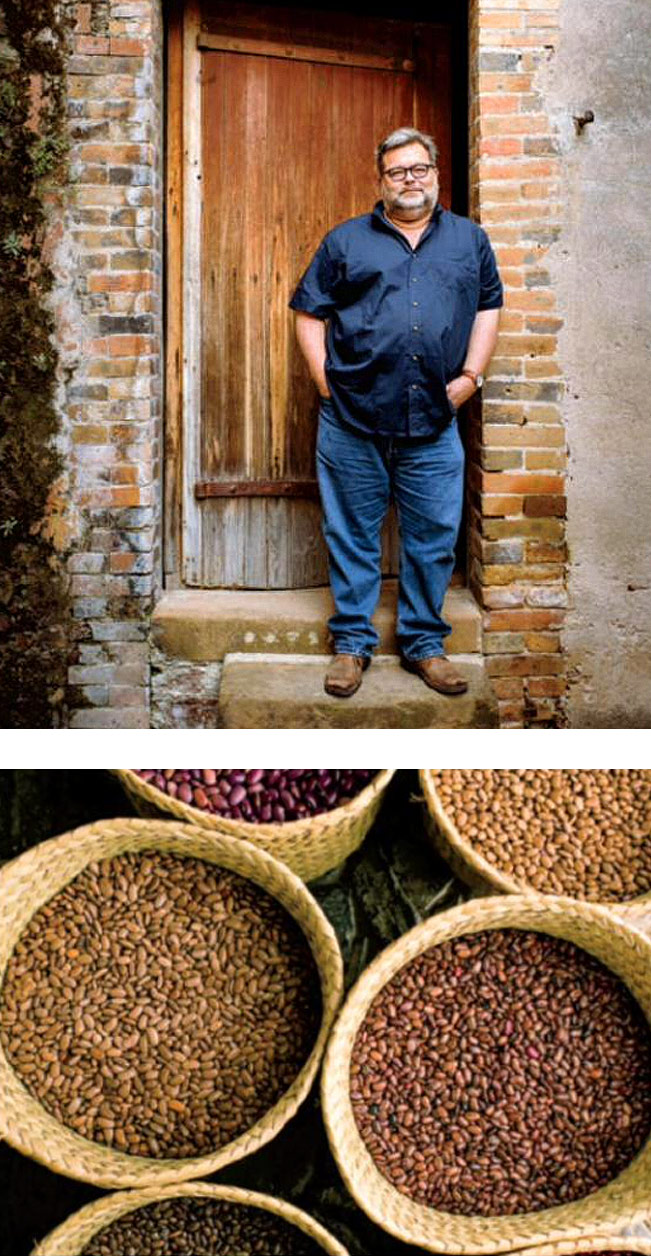

AAfter wandering through the huge open-air market of buniquilpan, in eastern Mexico, past stall after stall of chiles, cactus paddles, wild herbs, and what smells like a thousand toasted tortillas, we finally find the beans. Steve Sando runs his fingers through piles of them, hunting for discoveries, saying the names of the ones he knows. Dark red Sangre de Toro, bull’s blood. Glossy brown San Franciscano (“hints of chocolate and toffee,” he adds). Ojo de Cabra, the rare Eye of the Goat beans, with stripes and swirls of rich brown. Compared to the dull, plastic-bagged pintos and kidney beans in my neighborhood grocery store back home, these glisten like jewels.

Sando owns the California company Rancho Gordo, grower and seller of heirloom beans since 2002. Famous chefs across America (and some in Mexico) are among his most loyal customers. Thomas Keller, of The French Laundry, discovered Sando's beans a decade or so ago and has used them ever since. Rick Bayless of Frontera Grill, in Chicago, and Sean Brock, of Husk in South Carolina, order from him; so do Mexico City chefs Enrique Olvera, of Pujol, and Gerardo Vázquez Lupo, of Restaurante Nicos. The company sells many thousands of pounds a year through its two shops and mail-order business. Besides their taste and beauty, the beans are also unusually fresh: Unlike grocery-store beans, which can linger on shelves for several years, Rancho Gordo's beans are sold the year they’re harvested. They’re pricier than ordinary beans, but for an artisanal ingredient, they're affordable—a pound costs less than a small jar of fancy jam.

Although he's practically a patron saint of beans, Sando, 55, is anything but reverent. Sassy and gleeful is more his style. To customers who worry about the gas, he’ll say, “Gift with purchase,” and explain that more bean eating can help with that (he's serious; your digestive system adjusts). At his Napa shop, the walls are covered with steamy Mexican movie posters from the ‘40s and ‘50s. He has an unforgettable way of describing beans: “What's big and fat and creamy and makes everyone say ‘Wow’?” (Answer: ayocote blanco.)

With us in the market are Sando's Mexican partners, who've guided him to many a beany treasure. In 2008, while trying to source heirloom beans from Mexican farmers, Sando met Yunuen Carrillo Quiroz, an outgoing woman in her 30s, and steady, quiet Gabriel Cortes Garcia, her partner in life as well as business. Their company, named Xoxoc (sho-shoke), after xoconostle—sour cactus fruit, which they process several ways—was already set up for export to the United States. With Sando, they launched Rancho Gordo-Xoxoc Project, buy-ing from small-scale farmers and shipping their crops to California.

OOften, the partners find new beans and meet farmers in markets like this. Today, though, they're seeing beans they already know. Also, it’s time for dinner. So we hoist ourselves into Gabriel's SUV and drive for an hour through open country, past opuntia cactus and scrubby yellow-flowering shrubs. Finally we bounce down a rutted road to his family home, the place everyone calls “the hacienda.”

A gorgeous, crumbling manor built in 1708, the hacienda has multiple court-yards, a chapel, and soaring ceilings. Most of the rooms have skylights rather than windows, which gives them an almost spiritual glow. The building was in fact a Jesuit monastery at one time, Gabriel explains. Mostly it was owned by wealthy silver-mining families, until the Mexican Revolution swept them from power. Now Guadalupe (Lupe) Romero Vidal, the daughter of the worker who took over the hacienda, lives there with her husband, Javier. Her best friend, Isabel (Chabela) Cortés García, mother of Gabriel and his brother, Antonio, moved in when the boys were small. About 10 acres remain of the original 106,000.

An entire wing is devoted to food: a dining room that looks like a museum exhibit of colonial life from the 1800s; a dimly lit pantry; and three kitchens, one dominated by an enormous bracero, a stove of brick and polished stone that is original to the hacienda. Lupe sets a clay olla—a bean pot—over a charcoal-fueled grate in the bracero and begins to simmer a batch of the rich, almost fudgy Moro beans that Sando loves.

Over the next two days, Lupe and Chabela fire up pot after pot of heirloom beans, each with its own character. The gorgeous red Sangre de Toro, for example, have skins so thin they seem to melt as you eat them. They’re a delight straight from the pot, but the ladies show us how many ways they can be served. Chabela adds a spoonful of requesón—ricotta cheese fried with green chile and epazote, an earthy, addictive herb—and they’re transformed into dinner. To another bowl, she adds more broth, oregano, and fried tortilla strips, and it's soup.

Mashed with chile paste, purple ayocote morado beans fill envelopes of fresh corn dough toasted on a giant griddle. Puréed with their own broth, cocoa-colored bayo chocolate beans make a sauce for dipping tortillas. Creamy white ayocote blanco go into salad. Most of the beans can be used for any of these dishes. “You can reinvent the same pot two or three times,” Sando says.

AAs we watch the cooking, Quiroz, Sando, and Gabriel tell me the story of these beans. When trade protections disappeared in 2008 under NAFTA, cheap beans from the United States poured into Mexico, and heirloom farmers struggled to compete. Mexican grocery-store shoppers weren't interested in small lots of rare, indig-enous beans anyway. Many farmers pulled up their fields and migrated to the United States illegally, desperate for work. Their beans were in danger of disappearing too.

Sando decided to be a better neighbor. Rather than just buying beans once, or taking seeds across the border and growing them in Napa, he and Quiroz and Gabriel pay Mexican farmers to stay on their land and grow the beans they've raised for generations. One of the first people they worked with, Maria Bisma, used to grow her lovely gray rebosero beans all by herself. “She could only take as much to the market as she could carry on foot, 5 miles down the hill,” Sando recalls. When she joined the Rancho Gordo-Xoxoc Project, her grandson, who had been planning to cross the border to the United States, decided to stay and help her farm. “The solution to this whole thing is opportunity,” Sando says. “It’s not patronizing, it's not charity. It's validating what they do.” Eight years on, the project now works with 30 families all over Mexico. “Los que migren—those who migrate—now stay to work the fields,” says Gabriel. "They finally have money for what they know how to do. It's very good.”

We all sit down to dinner on the veranda at dusk, next to a courtyard of pink bougainvillea and butterflies. It's simple, incredibly good food built on corn and beans, the irreducible flavors of Mexico. As we eat, we talk—about family, the farmers, the beans they're still tracking down, and the satisfactions of the project. “We are creating a market,” says Quiroz. “I have the feeling of going down an ancient path and remembering as I walk. When the farmers plant, the past becomes alive again.” Sando agrees. But ultimately, he feels, it's neither sustain-ability nor respect for the past that gets people interested in heirloom beans. “The reason they buy these,” he says, “is because they taste great.”